Copyright: Iskra Research and Felix Kreisel

The article below may be copied and circulated but proper attribution of authorship is required.Nostalgia for Kolyma.

"Snow in May" by Kseniya Melnik

By Felix Kreisel

Earlier this year saw publication of a wonderful book of short stories, "Snow in May" by a young Russian-American writer, Kseniya Melnik. She came to the US at the age of fifteen, to Fairbanks, Alaska, actually. Melnik's birthplace in Magadan and point of landing in Alaska differentiate her from the majority of ex-Soviet emigrants who settle in New York, California and other densely populated centers. Her stories convey a certain fresh, or, at least, less explored point of view. This freshness is reinforced by the author assuming different characters, sexes, ages to narrate each story.

Melnik's stories take place in the town of Magadan, in Kolyma, or, if in the US, describe people from this remote place.

|

|

|

| Kseniya Melnik and the cover of her book. | Magadan is closer to Alaska and California than to Moscow. | Little Kseniya in Magadan. |

As the map of Russia shows, Magadan is very remote from the population centers of Russia: 5925 kilometers east of Moscow in a straight line. The nearest railhead lies across the 2000 km unpaved and deeply rutted Kolyma Highway, which can be traversed only by special trucks and SUVs equipped with large-diameter wheels. In this region of permafrost, roads are difficult and very expensive to construct. To reach Magadan, one must sail by boat either from the railhead in Vladivostok, or all the way from Arkhangelsk across the Arctic seas and around Chukotka, opposite the Bering strait from Alaska and the Kamchatka peninsula. The climate is subarctic, with up to six months of sub-zero temperatures, and the navigation season lasts a few summer months.

Melnik explains that the inhabitants feel that they live on an "island", far away from the mainland. Gold was discovered in the rivers of the Kolyma region a hundred years ago, but significant industrial collection and extraction began only in the 1920s.

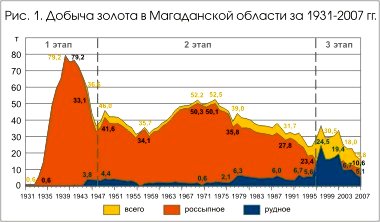

Then, in the early 1930s Stalin decided to use the millions-strong convict labor and developed the Gulag system of labor camps to search for gold, silver and many other precious stones, metals and industrial raw materials. Waves of Stalinist repression collected millions of Soviet citizens and distributed them across Siberia to the various labor camps. The gold mines in Kolyma received their share of convicts and gold production rose dramatically, peaking at 79 tons in 1938 (see figure below). By 1937, the camps in the Kolyma region were notorious for their isolation and brutal internal regime.

The reach of Moscow was weak there, at such extreme isolation, and the most steadfast and organized Oppositionists to Stalin, the Trotskyists, were not usually sent there because the GPU could not guarantee their isolation from the other prisoners, who might become "infected" with their ideas. The bureaucratic machine did make mistakes, and Alexandra Sokolovskaia, the first wife of Leon Trotsky and a firm Left Oppositionist spent some time there in 1937-38, before being returned to Moscow to be shot. The daughter of Adolf Joffe, — a close friend of Trotsky and a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee in 1917—1919, — Nadezhda, also spent some time in Kolyma.

Individual sympathizers of the Left Opposition were sometimes sent to Kolyma, among them, Varlam Shalamov, who wrote his "Kolyma Tales", dramatic short stories about life in the Stalinist gold mines. But better organized groups of steadfast Trotskyists were instead transported in 1937 to Vorkuta, where they were isolated and murdered in the spring of 1938.

No mention of Trotskyists is made in Melnik's stories; memory of them remains a tabu subject in Russia.

The demographic statistics for both the town of Magadan and the whole region are bleak. Up until the late 1920's there were no towns or villages, and the native population of Evenki and Yakut nomads was extremely sparse. Nuggets of gold were first discovered in the rivers of this region in 1915, but due to the remoteness of Kolyma it was not until mid-1920s that Soviet exploratory expeditions began. At first, there were no permanent settlements, only some dozens of prospectors coming by ship to the little harbor in Nagayev Bay during the summer navigation period to spend a few months panning and sluicing for nuggets of the precious metal.

But the Soviet bureaucracy needed not individual prospectors, but a massive gold industry, centrally directed, productive and obedient. Late 1920's and early 30's were a period of a wide-spread and mostly one-sided civil war on the recalcitrant peasants of Russia, Ukraine and other republics; millions of peasants were labelled Kulaks and sent east to Siberia. Stalin hit on the happy idea of using these unfortunates to dig for gold in the rivers of Kolyma.

Here is what the Russian version of Wikipedia has to say:

"The decision to create "Dalstroy" (Far East construction organization) was taken by the Politburo … on 11 November of 1931… The first echelon of detainees (at least one hundred persons) arrived at Nagayev Bay … together with free contract workers and armed guards on February 4, 1932. When the navigation season opened in the spring of 1932 there began large shipments of prisoners. Henrikh Yagoda (the head of GPU) gave an order to provide 16 thousand prisoners for Dalstroy. The plan was underfulfilled. By late fall of 1932 (end of the navigation season) 12 thousand prisoners arrived at Nagayev Bay. To sum up: none of the of the prisoners, neither their guards nor guard dogs survived the winter. The following year, more prisoners were transported to Kolyma by the fall of 1933; their survival rate was one out of fifty. In 1934, the prisoners were "luckier": more than half survived the winter." (https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B0%D0%BD)

|

|

Following Khruschev's Thaw in the mid-1950s the huge Gulag was slowly downsized, and the previous draconian method of convict and prisoner-of-war forced labor became impossible. The Soviet bureaucracy scrambled to find other, more palatable methods. A system of higher pay and better quality of life allowed Soviet authorities to retain many of the released slaves and turn them into willing gold miners, to attract families to these mining towns, to let the growing Siberian population enjoy much higher salaries and other perks. Indeed, during the 1960s and '70s Magadan and some other Siberian and Arctic towns became desirable destinations of internal Soviet migration.

By 1990, the population of Magadan region grew to 390 thousand persons. Then it began to shrink: in 2002, its population was halved to 179 thousand; by 2010 it shrank to 156 thousand. The town itself lost one third of its population, dropping from a high of 152 thousand in 1992 to below 95 thousand today.

Back to Melnik's stories

Melnik grew up in remote Magadan, but within the hothouse atmosphere of late Soviet period. Subsidized air travel connected the inhabitants of Magadan with Moscow, Leningrad and the rest of the Soviet Union; music schools, sports complexes, art schools were numerous, of high quality and accessible to most families.

One story illustrates the contradictions of living in this privileged and subsidized region of the Soviet Union in the 1970's. A school art librarian from Magadan is sent by the Ministry of Culture to an educational conference in Leningrad. The hugely expensive air journey across the length of the Soviet Union is subsidized by the government. On her return stopover in Moscow this librarian and mother of two is concerned to stock up on clothing, school supplies, photographic supplies for her husband and other hard to find "deficit" items for her family, including a bunch of exotic bananas.

The first story is told by a Magadan-born retiree, now living in California, who compares his life with the fate of his former best friend, who stayed in Russia. These two school friends met in childhood, studied at the same civil aviation institute in the European city of Riga, capitol of Soviet Latvia, vacationed in the Crimea together, skied together down the Magadan mountains, even married two girls-friends whom they met on one such Black Sea vacation. Life, the dramatic change of social regimes, its general push and pull drew them apart, and now the California retiree is afraid that his childhood friend might ask him for a money loan or a hand up. The California retiree's best friend is not even a human any more, but his pet dog.

Another story relates the experience of a 12-year old boy, a piano student in one of the music schools of Magadan, who has to perform on TV in front of an important audience. The conflicting emotions choke the boy, preventing him from playing a piece he had rehearsed dozens of times.

Although Sara Palin could not see Magadan from Alaska (the Kamchatka peninsula was in her way), Alaska and the Pacific coast of the United States loom large in the lives of the inhabitants of Kolyma, Kamchatka, Chukotka and the whole Far East of Russia. I mentioned the story of a Magadan aviation official. During Gorbachev's years of Perestroika he leveraged his connections in civil aviation into a lucrative business carrying passengers and freight between Magadan and the towns of Fairbanks and Anchorage, Alaska, later retiring to the United States.

An interesting story examines the lot of a Russian "mail-order bride" from Magadan, with her new American middle class husband. The married couple live in an Alaskan town, where the husband works as a high school history teacher. He collects Soviet memorabilia, which now includes, among World War II medals and First Aid kits, his pretty and well educated Russian bride. The story contrasts the woman's dramatic, event-charged life back in Russia with American "long, boring, happy lives".

The author shows great sensitivity and imagination, giving us insight into the inner life of these very different people. We see their dilemmas: to enjoy a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of a romantic date with a handsome Italian soccer player, or wait in line to buy bananas for her family; to struggle on as a woman surgeon in Russia, or live the empty life of an American housewife.

There are two distinct problems with the work of this writer. The first concerns the somewhat artificial language constructs her subjects speak. Obviously, they speak in Russian, their native tongue. The author is obliged to translate them into English, but she does it too literally. It appears to the reader as if these personages were speaking to you in broken English, like many immigrants do, translating their thoughts word for word. The effect is to give their narrative a strained character.

The second problem is less important. In attempting to emphasize that her stories are fictional Kseniya Melnik gives historical figures fictional names. In the story "Our upstairs neighbor" Melnik refers to the famous Russian singer Vadim Kozin, but gives him a literary name Makin. Well, Kozin is safely dead now; we all know that he was exiled by Stalin to Magadan in 1945 on the pretext of punishing him for homosexuality, but actually because Kozin could never bring himself to compose paeans to the dictator. Such fictionalization is especially irritating in Kozin's case because he was so famous in Russia and because he performed in front of Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt at the 1943 allied conference in Teheran. Fame like that cannot hide behind a pseudonym.

There is another, somewhat less distinct, yet more significant issue. The author describes Magadan and refers to the origins of the place with the discovery of gold, and the system of slave labor that Stalin instituted in the 1930's to extract this gold. She then mentions the high caliber of people one could meet in these regions: world-famous singers, scientists, engineers. Her own childhood embraced the last decades of the Soviet Union; people no longer starved or froze to death, but their material and political demands could not be satisfied by the stagnating Stalinist system.

Today, the miners of Magadan and their families may buy bananas in the local supermarkets. The shelves of some markets are well-stocked with Italian salami, Dutch Gouda cheese, pineapples and oranges. The lines are short since only a small minority of specialists can afford these goods. If you have a well-paying job, which some miners do, your apartment may resemble those in America or Germany, with large LCD TVs, Krups coffeemakers, Bosch refrigerators and gas ranges. However, some big things have gone out of the lives of Siberian workers: art museums, libraries, theaters, music schools, factory subsidized cultural clubs, municipal sports clubs that used to canvass local schools and enroll kids by the hundreds.

The civil aviation school in Riga has closed down, and not only for the reason that Riga is now in a different country, Latvia. Overall, air travel has plummeted in Russia and the other republics of the former Soviet Union. Shipping volumes, whether by air, rail, truck or ship have declined as well.

During the 1960's and 70's there was pulsating vitality in these former Stalinist killing grounds, people were coming to Siberia to develop its natural wealth, towns grew, new roads were built, kids were born. But capitalism is choking the life out of Russia's remote regions.

The universal laws of capitalist market have taken the whole Eurasia in their grip. There are no longer any free rides to Leningrad and Riga for art teachers, museum curators or college students. The number of flights from Magadan to Moscow has declined to one or two per day, and return tickets cost upwards of 800 USD. A vacation in the Crimea or Riga would cost thousands of dollars, and very few Siberians can afford this luxury. In a practical, everyday sense, Magadan, Norilsk and other mining towns in the Arctic and along the Siberian rivers have become much smaller, more isolated, many are dying out.

Kseniya Melnik is reluctant to acknowledge that her nostalgia is for the extinct Soviet Union, all the stupid contradictions of the bureaucratic regime notwithstanding. Her stories nevertheless constitute a rich and fresh look both backwards at the Soviet period and at today's realities.