The article below may be copied and circulated but proper attribution of authorship is required.

By Felix Kreisel, November 1999; Copyright: Iskra Research

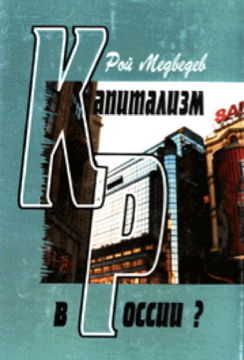

Roy Medvedev — Russian capitalism?

(Moscow 1998)

|

There was recently published in Moscow a book which aims to draw the balance sheet of the "first capitalist five year plan" in Russia and to present a summary of these events. The book was written by the well known historian and publicist Roy Medvedev. In this book he attempts to portray these developments both as a historian and as a sociologist. |

The names of brothers Medvedev, Roy and Zhores, are better known in the West than in the former USSR, especially among those "left wing intellectuals" who were close to the European and Latin American Communist parties. In the late 1960's Roy Medvedev gained fame in Europe for denouncing Stalinism from positions of "democratic communism". On the jacket of one of Medvedev's books, published in England in 1981, the "left" editor wrote: "The historian Roy Medvedev is internationally respected as a courageous and scrupulous socialist critic of his native Russia". |

|

Following the twentieth congress of the CPSU in 1956 and Khruschev's revelations the large Communist parties of Italy, France and some other countries simply could not keep on repeating the myths contained in the "Short Course of the History of the CPSU". The restatement by the official Soviet representatives of the obvious falsehoods in this mythology put the influential political parties of Italy and France into a ridiculous position. For these parties it became vitally necessary to find some new ideological basis, to rely on a if not truthful then at least plausible history of the Soviet Union and the international communist movement.

Following the rebellion in Hungary in 1956, the Sino-Soviet ideological split and the events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 within these parties there arose a mass ferment among the young activists and ideologists, there broke out furious discussions about the role of Stalin, about Trotsky's struggle, about Soviet history, about the varieties and alternatives of constructing socialism. The proclamations issued by the official Kremlin representatives could no longer satisfy the party rank and file, but the majority of the free Russian voices known in the West were anticommunist: Avtorkhanov, Solzhenitsyn, A. Zinoviev and others. Unlike them, Roy Medvedev spoke out as a communist critic of Stalinism, as a proponent of truth and socialist democracy. His famous book, "Let History Judge", published abroad in 1971 in a number of translations, tried to show that despite Stalin's cult of personality and the massive repressions, socialism, albeit of a damaged sort, was nevertheless constructed in the USSR. Throughout the 1970's Medvedev often traveled to the West, appeared in front of intellectual audiences close to the large communist parties of Europe. He reminisces that at that time he was supported by the communist parties of Austria and Italy, his books were published by the large printing house of the Italian CP, Riunite, and so on. The French and Italian friends of Medvedev today sit on the cabinets of ministers of these countries, their ideological roots rest on the world view of Roy Medvedev. We shall return to the evaluation of the earlier historical and political works of Medvedev, but now we shall turn our attention to the last book of this historian, published in early 1998.

Yeltsin's rule

Although the Russian book market is not short of literature, both memoirs and works of research, devoted to chronicling the social and political life of the past few years, the book by Medvedev stands out from the rest. Unlike the many superficial and tendentious compositions this author attempts to present an objective picture of recent events. To a large extent he succeeds.

The author feels no elation at Yeltsin's policies. He assumes a distinctly critical attitude to the past events, and this places him outside the two main political streams which up to this day dominate in Russian politics. Roy Medvedev assumes the mantle of a supporter of "democratic socialism", without, however, describing in detail what this means. Judging by this book he sympathizes with small enterprise and places his hopes for the country's future on it.

Despite a number of shortcomings the book contains many observations and evaluations which deserve to be pointed out.

Firstly, Medvedev clearly characterizes the nature of the popular attitudes at the end of Perestroika and points out that they were not at all sympathetic to capitalist reforms:

"The ideas of democracy and freedom were predominant in 1991, but the idea of capitalism never really took hold of the masses. The democratic movement was born of protest against the privileges of the partocracy, against the abuses of those holding power, against poverty and inequality. It was not only the inhabitants of the luxurious dachas who aroused hatred, but also the millionaire owners of the "cooperatives". The "new Russians", who had already made an appearance at that time, were forced to hide their wealth, and to display it only abroad on the resorts of the French Riviera. The Russian westernizing of 1990-1991 was a fleeting and shallow attitude of people who had already broken with the communist ideology but did not yet discover any new mobilizing national idea" (pp. 44-45).

Discussing the popular social movements of the Perestroika period he writes:

"The rank and file participants of the democratic movements in Russia were interested in the slogans of freedom and social justice, not at all in the goal of a market economy. Most of these people left the pro-Yeltsin movement by 1992, having felt first hand the results of shock therapy". "The population did not reject the idea of socialism and did not strive towards any "capitalist revolution". That is why the opponents of socialism thrust for political power, all the while hiding their final aims and proclaiming the goals of democratization and abolition of privileges, or even the slogan of a "better" socialism. It was only when the antisocialists came to power that they began to tear down the system" (p. 69, p. 129).

Medvedev points out that the initiators of capitalist reforms had no clear program of action and were driven for the most part by empirical considerations, believing that the market will somehow straighten everything out. He repeatedly quotes Gaidar, who in 1990 recommended to the leaders of the USSR "to shut their eyes tightly and jump off into the unknown".

The goals of the reformers were different from their public statements and their methods were far from democratic. Medvedev writes that

"Neither the effectiveness of management, nor modernization, nor the budget were among the goals of privatization during the initial years of the reforms".

The main goal of privatization

"was to create as fast as possible a layer of private proprietors who would then become a firm base for the new regime being created within the country"(pp. 176).

The actions of the reform team more resembled a conspiracy than the actions of politicians who had popular support.

"There was no openness at all in the preparation of Russian privatization. Chubais and all of his colleagues turned down all invitations to make public statements in the press" (pp. 174).

One of the prevailing phenomena of this period, as notes Roy Medvedev, was the fact that the dominant attitude among the masses was both a rejection of the old Soviet methods of rule by the CPSU, and also absence of popular support for conducting capitalist reforms. In this respect it is especially interesting to read his evaluation of the struggle in 1993 between President Yeltsin and the leadership of the Supreme Soviet under Rutskoi and Khasbulatov. Describing the various episodes of this prolonged trial of strength he records time and again that the population did not wish to support either one of the sides. Even when this opposition had reached its culmination and events were headed for an armed conflict this fact did not change:

"Despite the appeals of both sides the Muscovites exhibited a marked indifference to the slogans of both Yeltsin and Rutskoi. The parliamentary leaders counted on mass support, but it was not forthcoming" (p. 142).

Medvedev traces and documents the growth of alienation on the part of the Russian masses towards both the elite economic layers of the "new Russians" and the majority of the various political groupings:

"Within the country, there is taking place a process of general spiritual disorientation, a general disillusionment in the leaders, since immediately after the collapse of the communist myths in 1988-1991 there occurred an even faster collapse of the anticommunist and liberal-democratic myths and ideas" (p. 289).

In the chapter on "The catastrophic health of the nation", written on the basis of materials supplied by Roy's brother Zhores, a professional physician, the author truthfully describes the nightmare state of public health: the falling birth rates, the growing mortality, mass malnutrition and impoverished diets of the bulk of the population, disease epidemics, spread of alcoholism, — the range of devastating consequences resulting from the introduction of the market regime into the sphere of public health. Medvedev also notes that the capitalist government of Russia intentionally spread drunkenness among the people by introducing measures to increase the production and consumption of vodka.

In the chapter on "The economic consequences of the 13th "Five Year plan" Medvedev directs his readers to the well known statistics on the collapse of the Russian industry between 1990 and 1995. He writes:

"Only some of the extraction and refining industries, which oriented themselves to western export markets, escaped huge collapse" (p. 211).

All of the other sectors of industry, both heavy and consumer, experienced catastrophic collapse, and some even ceased to exist. Interestingly enough, to explain this collapse Medvedev quotes on the one hand a well known economist G. Rakitskaia, who declares that

"The President and the government had successfully and quite rapidly and efficiently executed the program of the International Monetary Fund. This program intended to destroy the Russian economy, to turn Russia into a colonial state with diminished living standards for the majority of the population, with mass unemployment, with uncompetitive industry, into a source of exceptionally cheap labor and cheap raw materials for the countries of the "First World" (p. 212).

Medvedev himself does not agree with this theory about the malicious sabotage of Soviet industry. In fact, he rejoins that

"In my opinion, the main reason for the failures of the "first capitalist five year plan" is a combination of the incompetence and voluntarism of those holding power, their inability to foresee the consequences of their actions, their haste and impracticality" (p. 213).

We cannot agree with either one of these two points of view. Both of them appear quite banal and spurious. The actions of the IMF, the World Bank or the Central Intelligence Agency, no matter how devilishly malicious, cannot explain the alternative paths of development of the economies of Japan and Russia, for example. It is much more important to trace the changes within the structure of world capitalism, the place of various countries within the world division of labor, the influence of geographic and climactic conditions, the consequences of the technological revolution in production, the political culture of a particular country, and so on. Medvedev's explanation is tautological; it explains nothing. Why is the Russian government so incompetent? Why do similar idiots, Yeltsin's identical twins, govern Kazakhstan, Ukraine and the other fragments of the USSR? For a supposed scientist such an explanation is completely inadequate.

The nature of the Soviet regime.

Let us look closely at Medvedev's picture of Russia. When describing the regime which had developed over decades of Stalinist dictatorship Medvedev turns away from an objective scientific analysis of the contradictions of the Soviet regime developed by Leon Trotsky. Instead he quotes such superficial critics of Stalinism like general Petro Grigorenko, or such belated reformists of the system of management as the academician Yuri Yaremenko. Medvedev repeats the well known criticisms of such economists as V. Seliunin, S. Shatalin, N. Shmelev and other publicists of the 1980's and 1990's with respect to the ineffectiveness of the Soviet economy, the love of gigantic projects, the enormous expenditures on armaments, and so on. For the most part these remarks repeated the earlier and more profound criticisms of Leon Trotsky, Khristian Rakovsky and the other Marxist Oppositionists, without, of course, referring to the authorship of these ideas.

During the nineteen thirties Trotsky wrote about the contradictions and disproportions of the Soviet economy, about the bad quality of the products, especially of consumer goods, about the low efficiency of industrial plants, about the high overhead of bureaucratic planning.

Basing himself to a large extent on the scientific work of Trotsky, the contemporary historian V. Z. Rogovin writes:

"Other economic disproportions were also accumulating throughout the country. The establishment of modern automobile plants coexisted with the tiny number and poor quality of roadways. The birth and rapid growth of new industrial cities was accompanied by the degradation of many older towns. Expensive theaters and palaces of culture were built at the expense of housing construction and contributed to the acute shortages of housing. In the towns there was on the average less housing per capita than before the Revolution" (Stalinsky NeoNEP, Moscow, 1994, p. 27).

In the "Revolution Betrayed" Trotsky wrote:

"While the growth of industry and the bringing of agriculture into the sphere of state planning vastly complicates the tasks of leadership, bringing to the front the problem of quality, bureaucratism destroys the creative initiative and the feeling of responsibility without which there is not, and cannot be, qualitative progress. The ulcers of bureaucratism are perhaps not so obvious in the big industries, but they are devouring, together with the co-operatives, the light and food-producing industries, the collective farms, the small local industries — that is, all those branches of economy which stand nearest to the people. "The progressive role of the Soviet bureaucracy coincides with the period devoted to introducing into the Soviet Union the most important elements of capitalist technique. The rough work of borrowing, imitating, transplanting and grafting, was accomplished on the bases laid down by the revolution. There was, thus far, no question of any new word in the sphere of technique, science or art. It is possible to build gigantic factories according to a ready-made Western pattern by bureaucratic command — although, to be sure, at triple the normal cost. But the farther you go, the more the economy runs into the problem of quality, which slips out of the hands of a bureaucracy like a shadow. The Soviet products are as though branded with the gray label of indifference. Under a nationalized economy, quality demands a democracy of producers and consumers, freedom of criticism and initiative — conditions incompatible with a totalitarian regime of fear, lies and flattery.

"Behind the question of quality stands a more complicated and grandiose problem which may be comprised in the concept of independent, technical and cultural creation. The ancient philosopher said that strife is the father of all things. No new values can be created where a free conflict of ideas is impossible. To be sure, a revolutionary dictatorship means by its very essence strict limitations of freedom. But for that very reason epochs of revolution have never been directly favorable to cultural creation: they have only cleared the arena for it. The dictatorship of the proletariat opens a wider scope to human genius the more it ceases to be a dictatorship. The socialist culture will flourish only in proportion to the dying away of the state. In that simple and unshakable historic law is contained the death sentence of the present political regime in the Soviet Union. Soviet democracy is not the demand of an abstract policy, still less an abstract moral. It has become a life-and-death need of the country" (chapter 11).

The economic conceptions of Medvedev

Medvedev's world view vividly expresses the general conceptions of Stalinism, a way of thinking which in a formal manner, by fiat, abstracts the development of a concrete society and country from its historical, geographical, cultural and class conditions and tries to force fit contradictory, often incomplete and rudimentary phenomena into a dictionary of simplified pseudo-Marxism. We have already pointed out that Stalinist ideology defines socialism as the nationalization of the means of production plus the bureaucratic management of the country. What we see, in essence, in Medvedev is a reverence for the powerful state and the official who rules the state and its economy. Sometimes in his fetish of the state Medvedev reaches absurd extremes, for example he counts among such "powerful" states South Korea, Singapore and Vietnam. The "might" of these states consists in the ability of their compradore capitalists to mobilize their working classes and their countries' natural resources more efficiently than their competitors to serve the interests of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and Wall Street.

It appears to us that the main question consists in the possibility of building a socialist society within one country. Let us consider the way Medvedev thinks about this subject:

"The economic system of our country was influenced not just by the dogmas of the nineteenth century but also by the dogmas of the twentieth. The Communist party was constructing a socialist society in a single concrete country while surrounded by states which were far from friendly. In such conditions the national economy had to be maximally self sufficient and could not utilize the advantages of the international division of labor" (p. 13).

We shall see later on that in his earlier works published abroad Medvedev stated that the classic nineteenth century "Marxist dogma" presupposed that socialism would be constructed on an international, not on a national scale, and that this dogma was wrong.

But wait a minute, if the Marxist dogma of the 19th century — up until Luxembourg, Lenin and Trotsky — stressed the idea of a European and world revolution and of world socialism, then in the 20th century, if we believe Medvedev, this international dogma was supplanted by a patriotic dogma of an insulated national socialist society. In his works of 1970's and 1980's Medvedev based himself on this postulate, common to all the varieties of Stalinism: the traditional Soviet variety in the spirit of the "Short Course of the History of the CPSU", the Khrushchev "anti-cult" variety, Maoists, Eurocommunists, "socialists with a human face", and so on.

In the final analysis we are not interested in following this or that "dogma" but in examining on the basis of continuing experience which of these two contradictory world views — about the international nature of both capitalism and socialism, or about a nationally delimited development — which of these best reflects the actual development of human civilization. We affirm that the whole experience of the twentieth century confirms the "dogma" of Marxism about the international nature of capitalism, about the world market, the world division of labor and the hegemony of the world economy over any national economy, even the largest.

The development of railroads and automobile highways, the digging of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the Panama Canal in 1914, the development of passenger and cargo aviation, the containerization of shipping in the past thirty years, all of these technical achievements serve as powerful factors which unite all the local and national economies into one world economy. The very recent developments in communications, computers and industrial robotics also lead in the same direction. One can only reflect with astonishment at the foresight of Marx and Engels, who one hundred and fifty years ago had shown us the direction of change and development of capitalism: from the local and the nationally delimited to the worldwide.

Medvedev's thought is imprisoned within the schematic and stereotyped nationally delimited approach, so characteristic of Stalinism:

"The main reason for NEP's success was that there survived within Russia millions of people — "petty proprietors" — who still maintained not only the will but also the ability to work within the conditions of the market and of private property" (p. 17).

This is a banal and superficial idea. Medvedev ought to explain why in Germany at the same time (the 1920's) the millions of "petty proprietors" could not restore the German economy to its pre-War dynamism, or why the USSR exhibited phenomenally successful growth rates during the first two five year plans, or why China in the past twenty years had developed a massive capitalist sector, despite the previous decades of "Cultural revolution" and the extermination of "petty proprietors". I do not wish to say that the presence in Russia during the twenties of a large layer of petty bourgeoisie, which had developed under pre-Revolutionary market conditions, had no effect on the quick expansion of market production, but Medvedev gives us a much too simplistic, and hence incorrect explanation. The NEP was especially effective during the restoration period of 1921 through 1926. But the restoration of the Russian economy to the pre-War level of 1913 could not be the final goal for the Bolsheviks. The further development of the USSR had to be conducted under conditions of competition and struggle between two contradictory economic principles: plan and market. Such a dialectical approach corresponds to the actual development of organizational and managerial technology used within the capitalist economy of the twentieth century. Any sizable capitalist firm utilizes planning, makes long term prognoses of the market conditions under which it will need to operate, and this on the international, not on a local or a national scale. The Left Opposition during the nineteen twenties proposed a program of extensive and wide scale industrialization financed by an increased taxation of the wealthier peasants in the country and the petty bourgeoisie in the cities. This program could have saved the Soviet people from the shocks and cruelties which resulted from the eclectic zigzags of Stalin. It is noteworthy that Medvedev in each one of his many books finds some reason not to explain to his readers the essence of the Left Opposition's program.

And here are a few more samples of Medvedev's spirit of national reformism:

"As is well known, the Republic of Tatarstan has achieved maximum independence by not retreating from the policies of state regulation of the economy, and this in spite of much criticism addressed at Mintemir Shaimiyev for his "conservatism". Beginning in 1996 the industrial production within the republic grows by 2-3% annually. The pensioners receive their pensions on time, the workers and employees receive their salaries. Everyone knows that the economic successes of Moscow are explained primarily by the competent economic policies of the Moscow government and mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who had long ago rejected the recommendations of Gaidar, Chubais and the International Monetary Fund. The Moscow government quite confidently controls and regulates the economy of the capital" (pp. 20-21).

"The Russian "market romanticists" obviously overestimated its possibilities and its role. It is far from a panacea or a universal solution. The market has nowhere become the sole regulator of the economy, and in the majority of the world's countries is not even today the major influence on economic relations. Even in the United States, which are considered to have the most developed market relations, following the Great Depression the regulatory role of the state has remained so large that the extreme supporters of monetarism accuse America of being socialist. Market relations can not only stimulate, but may also stifle the national economy of states which are late comers into the world economy. If they did not base themselves on the mighty support of the state these countries would be unable to survive the competition against the monsters of world economy. Who devised and helped South Korea execute its five year plans of economic development? Even more impressive are the successes of Singapore where the rational policies of state and social regulation play a major role in economic development. I am not even mentioning the successful development of China and Vietnam. But even among the states of the CIS the most successful economic achievements have been achieved in Belarus and Uzbekistan, where the regulatory role of the state exceeded Russia's" (p. 48).

"I shall not cite here the experience of China, where in the past twenty years the gross national product has grown five or six fold and the material quality of life has gone up four or five times for its population of 1.3 billion. Neither shall I refer to the experience of the postwar Germany and Japan, which in the aftermath of military destruction and occupation succeeded in the course of twenty five years not only to overcome the destruction and chaos, but to emerge as the economic leaders of the Western world" (p. 9).

On page 54 Medvedev again refers to Singapore in glowing terms and agrees with the sentiments of the Singaporean ambassador to Moscow that

"The history of the development and flourish of Singapore is a triumph of the will, organization and discipline, the readiness to use in the interests of the cause any possibility, a demonstration of the success of the social, economic and political technology and ability to overcome the absence of resources. Singapore symbolizes the hope for other developing countries that they may also achieve similar results".

Medvedev continues:

"In 1960-1995 the per capita Gross National Product of Singapore increased by more than fifty times. This small Asian country, lacking in resources, needed just thirty years to transform itself from a developing into a developed state".

Capitalism after the Second World War

Like Medvedev, we shall refer to the example of Germany and Japan. But we shall use this example to show the unscientific and ahistorical nature of Medvedev's method. Devastated during the Second World War, Japan and Germany arose and flourished in conditions of a general world wide economic expansion, when the world market grew and spread out, when the demand for industrial goods rose almost continuously, when the vast accumulated resources of American capital spread throughout the rest of the world and fed the Marshall Plan, the Cold War and the miraculous expansion of the credit system and mutual budget deficits. A significant role in the flowering of the German and Japanese capitalism was played by the nationally delimited psychology of the working class of these countries. Insofar as the German and Japanese workers considered themselves as, first and foremost, Germans and Japanese, they blamed themselves for starting the War and thought of themselves as conquered and defeated people. To that extent they were willing to tighten the belts around their thin waistlines, work all the harder and forego normal wages and the good life. This factor of national abnegation played a significant role in the reestablishment of the Japanese, German and Italian capitalism in the post-War epoch.

That epoch has passed. The industrial growth of South Korea took place in the 1960's and 1970's under conditions of industrial stagnation within the older centers of capitalism, especially in the United States. The expansion of shipbuilding yards and steel plants in Korea took place at the expense of closing the older analogous plants in the US, Germany and Italy, as a result of the transfer of capital from the old metropolies into the more profitable and fast growing industrial zones of Asia.

China

Many of these references about the prosperous Vietnam and China or about the comfortable Moscow and Belarus read somewhat ridiculous only a year and a half after they were written. Numerous crisis tendencies are maturing in Vietnam and China. The whole development of China over the past two decades is tightly bound up with the integration of the coastal regions of the country with the world economy. Streams of international capital flooded into these areas to utilize the cheap labor and the comparatively cheap raw material resources for production of goods which are eventually destined for sale on the world market. The introduction of bourgeois regime in agriculture, for example, has thrown tens and hundreds of millions of former peasants out of their usual atmosphere of a primitive almost natural economy. And while new plants made to the latest American and Japanese specifications are being assembled in the coastal regions, the interior provinces of China are full of ancient industrial plants producing mountains of overpriced metals, semi-finished products, obsolete televisions and bicycles. According to recent reports the consumer market is shrinking, there has begun a deflation of the market prices for mass consumer goods, more that half of Chinese industry is working at a loss, the greater part of state banks are in reality bankrupt. In the social sphere the consequences of capitalist regime are driving rises in costs of housing, education and health benefits so that masses of Chinese workers and peasants are deprived of basic needs. The monumental growth of the Falun Gong society, a semi-religious mystical association whose membership numbers many millions, only shows the pessimistic moods of the Chinese masses, especially the elderly and the pensioners, who are virtually thrown into the rubbish heap and feel themselves alien in their own country.

Under conditions when throughout the whole region of South East Asia there is growing a crisis of sales glut and overproduction the expanded productive capacities of China risk to become, so to speak, suspended in mid-air. Something similar, albeit on a smaller scale, is taking place in Vietnam. The "communist" partocracies of both countries are attempting a tricky balancing act to maintain control over their unstable, maladjusted, creaking and cracking machines of state. At the same time they are attempting to establish the right to inheritance, to divert the state property which remains under their control and to transfer the controlling stakes in the various businesses into the hands of their relatives. The contradictory interests lead to a series of compromises between the state control and the interests of the individual enterprises which are working in market conditions, between the national interest and the interests of the various provinces. But these compromises, eclectically forced upon the so called "communists", immediately turn into new threats to their rule. The "Chinese model of moving from socialism to capitalism", which is today lauded by Medvedev (ten years ago he sang a different tune and extolled Gorbachev's methods over those of Deng Xiao Ping), is threatening in the very next period to undermine the national cohesion of China and negate the results of the huge sacrifices which the long suffering Chinese people made during the twentieth century.

Singapore

To tell you the truth, I found Medvedev's references to Singapore laughable. Ridiculous, and yet so characteristic of the intellectual decay brought about by Stalinism. Medvedev sees in Singapore an example of a "successful and mighty" state. But every child learns in a geography class that the state of Singapore is a miniscule archipelago which consists of the island of Singapore and fifty more tiny islets on the end of the gigantic Malay peninsula, the total area of which comprises 633 km. square and whose population numbers 3.2 million (in 1998). Formally, it is an independent state; in reality, it is a former garrison post of the British empire created by the British according to the same principle as Hong Kong and Gibraltar: to oversee and control the extensive territories of Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and Indochina. There are no natural resources within Singapore, even drinking water and foodstuffs are imported. Agriculture and fishing contribute only 0.2% of the Gross National Product (1998). Formally Singapore is run by a one party government, but in reality it is run by the Monetary Authority of Singapore, a council of the leading bankers and industrialists.

In truth, Singapore is a perfect example of the "free enterprise zones" which were created by the world market in the last few decades. In 1967 the American electronics firm, Texas Instruments, built a semiconductor factory in this city-state utilizing the excellent natural harbor, the central geographical location of this port at the crossroads of the shipping sea lanes and the cheap and obedient labor power available in the region. This firm was followed by others and Singapore grew into a central base for locating offshore plants of giant multinational corporations in the industries of electronics, especially the assembly of magnetic computer disks, in oil refining and petrochemicals, and in pharmaceuticals. Singapore's workers compose primarily immigrants and their children from China, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and other countries of South East Asia. Their status as immigrants and the mix of tribes, races and religions tended to make these workers more subservient to the will of capital, easier to exploit.

The whole history of Singapore following the granting of sovereignty from Britain (one cannot speak in this case of any struggle for national liberation) is an example of how the formally sovereign backward countries become totally subordinate to the pressures and dynamics of the world capitalist economy. The compradore capitalists of Singapore are only the local representatives of the transnational corporations, banks and other agencies of imperialism. The role of trade unions is strictly circumscribed, opposition parties are outlawed, democratic freedoms do not exist, elections are a farcical masquerade. The admiration of Medvedev for the "wise policies of this mighty state in the area of state and social regulation" which has brought about the wonderful "transformation from a developing to a developed country" appears somewhat quaint, for, after all, Medvedev usually poses as a supporter of small enterprise, a proponent of nice, rosy colored, democratic, social, mixed semi-capitalism.

Moscow Tatarstan, Belarus, etc.

Let us now consider Medvedev's arguments in favor of state regulation of the national capitalist economy and try to extract a rational kernel from the chaff.

Firstly, we must immediately point to the absurdity of Medvedev's admiration for the apparent well being of Moscow. Under Stalinism the capital of the Soviet Union lived much better than the country in general. This occurred to a large extent because the ruling bureaucracy, a good portion of which lived in Moscow, appropriated for itself the choice pieces produced by the national economy. In any case, the population lived considerably better in the capital than in the provinces. During the past decade the production of consumer goods has fallen everywhere, in Moscow perhaps even more sharply than elsewhere. But the relative advantage in average per capita living standards between an inhabitant of Moscow and the other Russian provinces has even increased and has reached unheard of proportions. A couple of years ago I came across a calculation made by a Russian investment firm which showed that in 1996 the per capita income of a Muscovite was three to four times greater than that of an inhabitant of Rostov, Riazan or Volgograd. In addition, as we all know, the payment of wages and pensions is more timely in Moscow than in other places.

What is the reason for this comparative well being? We do not wish to give the overly simple answer that the Moscow bureaucrats rob all the foreign credits and loans extended to Russia as a whole, skim off the excise and income taxes and so on. This, of course, takes place, but Medvedev expresses his admiration not for these criminal incomes but for, so to speak, the effective municipal government, the statesman like wisdom of mayor Luzhkov, the organization of the economy of the capital, and so forth. Is there some truth to in this argument?

Moscow receives about 80% of all the foreign direct investment, the capital houses the head offices of the international firms which do business with Russia, the foreign currency expenditures of the foreigners and the "new Russians" both, the services which demands and which receives the new nobility of the capital, all of these sources of income fill the municipal treasury and help to secure and preserve the various municipal and communal services at a relatively high level. There is a great deal of modern office construction in Moscow to house the offices of both the Russian giants like Menatep and Gazprom and the branch offices of the foreign firms and banks, new hotels are built and older ones renovated. Tens of thousands of "New Russians" live in Moscow; they go shopping and visit the discotheques, they hire personal chauffeurs and bodyguards, doctors, lawyers and prostitutes, they send their children to kindergartens and private schools of a superior type, they visit the theatres and the museums. In this way around these nouveaux riches there are employed and fed hundreds of thousands of "almost normal Russians". All this business provides a certain basis for the city economy, for the municipal transport, for the maintenance of sanitation and sewage systems, for maintaining some systems of public health and education, and so on.

But the question arises: is this business productive, does it pay for itself in the long run? Are all these luxurious discotheques and casinos, banks and jewelry stores glittering with chrome and glass necessary for the development and expansion of the Russian economy? Not at all, just the reverse!

When, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow lost its influence in the republics of the former USSR the foreign firms opened direct relations with these new countries and curtailed their representation in Moscow. The very same process is taking place now in relation to some of the Russian provinces: direct links are expanding between the Russian producers of export commodities and their partners abroad. Airplanes from Frankfurt and Amsterdam fly directly to Yekaterinburg and St. Petersburg without stopping in Moscow, loaded trains proceed directly from the producing factories to Europe, also, if possible, leaving Moscow to the side. In order to save money the Russian compradores and their foreign counter-agents attempt to avoid the control of the greedy bribe takers in Moscow.

Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod and many other Russian provinces try to conduct at the present time an economic policy independent of the federal government. After the system of the GKO (Russian state bonds) reached an impasse some four years ago and the state budgeting of provincial governments was cut to the bone, the various provincial governors attempted to get around the central government and started to borrow money directly on the international credit market. In China we also saw the various provincial governments set up their own "investment corporations" and float their own quasi-sovereign bonds on the world market. Gitic, one of these corporations from the province of Guandong, has already gone bankrupt. Recently the Financial Times reported that the Russian province of Nizhny Novgorod (until recently led by a darling of the Western financial circles, the "reformist" Nemtsov) has asked its creditors to extend its payments schedule. The same article warns its readers that because of the international difficulties with the loan payments by Equador, Brazil and some other "developing countries" the conditions of lending to Moscow and the other regions of Russia will tend to become more stringent. We may safely leave it to the reader to deduce the future trends of such local governmental credit and financial operations.

The development of capitalist state

If we examine the development of capitalism on a broad historical scale we see that during the epoch of the initial accumulation of capital in Holland, England, France, the United States, etc. the more farsighted bourgeois extolled such virtues as hard work, everyday thrift, sobriety, strong family bonds, and so on. During the many generations of an incremental and slow development of bourgeois society there arose complete new religions to fit these moods and attitudes: Lutheranism, Puritanism, Calvinism and others. In the sphere of politics in the countries of the slowly and elementally rising bourgeoisie this new class strove to limit the interference of all government (the royal authority, the greedy hereditary nobility, the equally greedy and wasteful church nobility) in the running of the society and the country. This demand was expressed in the ideals of a cheap government, the bourgeois republic and liberalism. A rationalization of government and a regime of economy and thrift were needed to speed up the capitalist accumulation and an expansion of the productive forces. The modest and hard working English Puritan saved every penny in order to reinvest it and to increase his working capital.

Unlike the capitalist accumulators of past, the contemporary Russian capitalists have no outlook for the future: they burn through yesteryear's (Soviet period) accumulations and today's earnings as if there were no tomorrow. The apparent well being of Moscow rests on quicksand.

Medvedev contrasts the debauchery of Yeltsin's Mafia entourage with the more disciplined and conservative rule of Mintemir Shaimiyev in Tatarstan, Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus and Islam Karimov in Uzbekistan. The relative security of Tatarstan rests on its oil production and on its relatively secure access to the Russian oil pipelines to Europe and to the markets there. President Shaimiyev succeeded in achieving a relatively favorable division of spoils with the bandits, beg your pardon, with the government in the Kremlin and with the mullahs in Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan.

But even this relative security is totally dependent on the pressures of the world market. The autumn (of 1998) fall of the world prices for oil to 11 USD per barrel dealt a sharp blow to the income of the Tartar oil company, Tatneft, and to the receipts of Shaimiyev's treasury. This oil price drop, incidentally, was also a major factor in hastening the Russian financial default of August 1998. The oil prices have since risen to a relatively high level of 20 USD and Tatneft is currently profitable. However, this does not at all guarantee a long term basis for the development of the Tartar economy. Recent reports in the financial press indicate that during the oil price troughs of 1997 and 1998 the Tartar government floated huge loans on the international financial markets via some front companies (mainly through Tatneft). These IOUs signed by Tatneft and Tatarstan have placed the population of the republic into a subservient position with respect to the world stock markets. Thus, even the "powerful", in Medvedev's opinion, Tatarstan is in reality no more than a chip tossed hither and there on the stormy waves of the world economic ocean.

As to Belarus, Uzbekistan and some of the other Russian provinces known for the rigid discipline imposed by their governments and promoted by Mr. Medvedev, well, the clouds are gathering there as well. The police dictatorship of the nomenclature and the system of strict rationing are only able to slow temporarily the decrease in production by comparison with the Russian collapse, they may stretch out the stagnation, but they are unable to raise either industry or agriculture up to world market standards. These regions are destined for an eventual collapse as well.

In general, the conditions facing backward states continues to deteriorate. Independently of the conjunctural changes in world prices for the export commodities of a given country (oil, gas, metals, cotton, coffee and so on) they are completely dependent on the world market, subject to the pressures coming from the imperialists and their economic institutions.

The benefits of "state capitalism"

But we have promised our readers to find a kernel of sense among the tangled arguments of Medvedev with respect to the state direction over the economy. It is there, but it can be found only in the context of world history.

The development of capitalism in Britain took place on an island where the naturally expanding bourgeoisie had no need for a standing army. In the 17th and 18th centuries the bourgeoisie sought a cheap government, limited and simplified legal system, a republic, an unpretentious and modest church. In 1649 Cromwell cut off king Charles' head in order to secure for the bourgeoisie its predominance over the royal court, to put a stop to the pretensions of the nobility, to end the domination of medieval habits, the hereditary hierarchies of feudal lords and princes of the Church. In 1793 the French bourgeoisie did the same.

But by the 19th century, when the proletariat had entered the political scene, bourgeoisie had realized that in its deadly struggle with this new enemy it requires a strong authority, an army, state police, prisons and all the other paraphernalia of oppression. For a national unification of Germany in the epoch of expanding national conflicts and imperialist economics history required the services of the "Iron Chancellor", Bismarck, who in his turn was forced to put through a whole series of labor and social legislation so as to neutralize the German working class during this period (1860's — 1870's).

To this political factor there must be added an economic one. In his work "Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism" Lenin noted the extremely important role played by state power in the economic life of each country. Imperialist politics gives a continuos impetus to the strengthening of the executive branch (President, Prime Minister or king) at the expense of the Parliament and the more democratic legislative branch.

It must be said that in Russia the development of capitalism proceeded somewhat differently from Europe and the role of the state in pushing along and directing the economy has been much greater ever since the time of Peter the Great. The poverty and relative sparseness of population dampened the elemental development of trade, manufacturing and the bourgeois market. On the other hand, the constant external threats forced the government into undertaking wide ranging programs to organize the industrial development of Russia.

Medvedev cites the example of South Korea, the capitalist government of which has been developing five year plans and assisting the local development of industries by means of financial, excise and taxation schemes, and also — we simply cannot fathom why such an excellent social-democrat had forgotten this important factor — through the cruel police repression of strikes, trade unions and opposition parties.

The example of South Korea probably appeared unassailable to Medvedev during the writing of this book, a year and a half ago. But now, after the economic crisis in East Asia and Korea especially, when the mightiest of the industrial combines (chaebol) like Daewoo and Hyundai had declared insolvency and their holding companies are busy selling off the pieces to satisfy their creditors, now such arguments lose much of their potency. In the West, the specialists are busy reevaluating precisely this "state capitalist" characteristic of the "Asian tigers". Up until recently most mainstream economists referred to the successes of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan and advised the United States to follow their example. Now, these pundits label such state aid "crony capitalism" and accuse it of prolonging the survival of backward, ineffective and uncompetitive trusts in these countries.

We may thus summarize the rational kernel in Medvedev's argument: the historic development of capitalism leads from the less organized and the more spontaneous forms to the more organized and centralized forms. Under capitalism, during bourgeois rule this trend leads to the diminution of real democracy, to a more complete dictate of big capital. In the United States, which usually show us the future of capitalism, democracy has become a formal pretense: the two party system has long ago resulted in an extremely narrow range of discussion in the mass media, to elections without a choice, to the absence of any public debate about any real differences of opinion.

Under socialism, the world integration and the planned character of modern industry must lead to a vivid expansion of democracy, to passionate debates among the broad mass of people about what the industry must produce, how to produce it, how to avoid the negative side effects of production.

We have paid a good deal of attention to economic analysis of Medvedev's book because his mistakes are typical of the false perspectives of the whole Russian establishment. The views prevailing in the Russian press are vulgar and contradictory, the analysis of events skims the surface, does not try to penetrate to the roots of the problems. As a result, Medvedev, who yesterday posed as an "anti-Stalinist" and a "socialist democrat", today praises the capitalist dictatorship in South Korea and acclaims the statesmanship of … Stalin. That is correct, Stalin!

We already pointed out that in this book Medvedev does not see any need to inform his readers of Trotsky's analysis and of criticism of Stalinism from the left, although he cites numerous opinions of the right: he quotes P. Miliukov, approvingly refers to Stolypin's reforms, quotes the ideologues of monetarism Von Hajek and M. Friedman, refers to P. Struve as a liberal. But what is even more shocking to the uninitiated is a reevaluation by Medvedev of Stalin's role in the development of the Soviet Union. On page 98 Medvedev writes:

"The monetary reform conducted in December of 1947, two and a half years following the conclusion of the War, was much more humane than the monetary policy of Gaidar's government. … When choosing from among the different ways to execute this reform Stalin picked the alternative which most fully defended the savings of the population".

Here we see the trajectory of Medvedev's thinking. In the past he criticized Stalin and Stalinism from the "left"; now he moves to a justification of his totalitarian dictatorship over the working class, towards extolling the "wise dictator". In order to understand this change in his ideological goalposts we need to examine the past historical conceptions of Medvedev. Such an analysis will be additionally useful since these conceptions constituted an important ideological stream in the world view of Eurostalinism and of the "Perestroika Communists" inside the former USSR.

See also: Roy Medvedev — Neo-Stalinist semi-liar